At long last, Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens on Cooperstown path

It won’t happen this year.

Maybe not next year, either.

But it’s finally happening.

For the first time since their names first appeared on the ballot in 2013, Barry Bonds and Roger Clemens are virtually assured of stepping onto that stage in Cooperstown, N.Y., in the next few years and earning induction to the Hall of Fame.

The Hall of Fame voters, a constituency of about 450 veteran members of the Baseball Writers’ Association of America finally have seen the light.

It has been absurd to keep the finest hitter and pitcher of their generation out of the Hall of Fame because of their dalliances with performance-enhancing drugs.

Bonds and Clemens, who haven’t eclipsed 45.2% in the balloting, have each received 70% of the votes, according to early polling results compiled by Ryan Thibodaux, 5% shy of what’s required for election. It won’t last, of course. Their numbers will drop once all of the votes are counted — with Tim Raines and Jeff Bagwell virtual locks to earn induction when results are announced Jan. 18 — but for the first time Bonds and Clemens will receive a majority of the vote, paving their way to Cooperstown.

The BBWAA finally recognizes the absurdity of keeping Bonds and Clemens out of the Hall of Fame but letting Mike Piazza, Bagwell and soon Ivan Rodriguez into the hallowed halls.

And, please, enough of the notion that the BBWAA is changing its stance on Bonds and Clemens simply because former commissioner Bud Selig was voted into the Hall by the 16-member veterans committee a few weeks ago.

MORE HALL OF FAME COVERAGE

Say it ain't so: Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens nearing Hall of Fame threshold

Hall of Fame case: Pudge Rodriguez will get in, but might have to wait

Hall of Fame case: Trevor Hoffman will find the Mo to get in

Hall of Fame case: Is Curt Schilling now his own worst enemy?

It’s nonsense to call Selig an enabler or accuse him of being solely responsible for the steroid era because it happened under his watch.

Sure, Selig and union chief Don Fehr could have stopped it. So could have every owner, front office executive, manager, coach, training staff member and physical therapist, too.

No one cared because the cruel fact is that steroids, human-growth hormone and androstenedione were good for the game. The drugs helped produce unbelievable performances. The better the performance, the more the team won, the bigger the crowds.

There were few, if any, complaints when Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa, with their juiced bodies and bulging muscles, helped save baseball in 1998 with the home run chase that captivated the country, with each eclipsing Roger Maris’ single-season home run record.

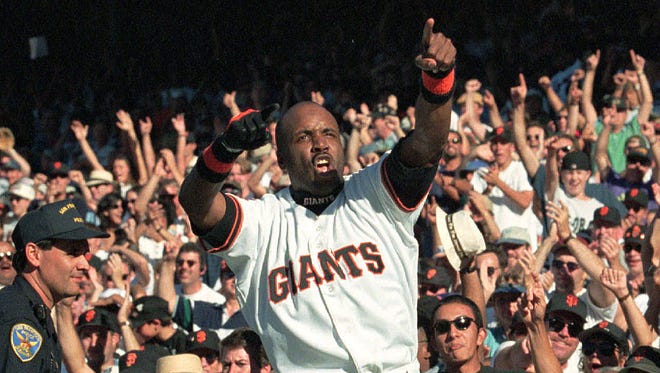

It was no different for Bonds or Clemens. There was never a peep out of the San Francisco Giants, who watched Bonds, a seven-time MVP, pack the joint every night en route to breaking Hank Aaron’s all-time home run record. Clemens, a seven-time Cy Young Award winner, was viewed as a savior wherever he went, winning two World Series with the New York Yankees and pennants with the Boston Red Sox and Houston Astros.

Really, when you think about it, there wasn’t a single team during the steroid era that publicly complained about any of its players using PEDs. The performance-enhancing drugs made players much more productive, not only helping their careers but also aiding the franchises that employed them.

Like Bonds and Clemens, Piazza, Bagwell and Rodriguez never confessed to steroid use despite significant physical transformations. They tried to tell us it was because of the use of androstenedione, the same drug McGwire admitted taking. Only Rodriguez was directly accused, when former teammate Jose Canseco claimed in his book that he shot up Rodriguez with steroids. Rodriguez vehemently denied the allegations. He later lost 30 pounds over one offseason — right before the 2005 season, when baseball began testing for steroids.

Anyone involved in the game had to be naive or stupid to not realize that what they were witnessing on the field or in the clubhouse was unnatural.

It doesn’t matter who escaped federal investigations or their name appearing in the grossly incomplete George Mitchell report or revenge from scorned trainers or clubhouse attendants. The coldhearted fact is that hundreds and perhaps thousands of players used performance-enhancing drugs during the steroid era, including at least a handful of players already in the Hall.

We’ll never know exactly who was clean or who was dirty, but statistics and record performances will tell us we do know who the best players were during the steroid era.

There are only four players on my Hall of Fame ballot who were never under the suspicion of performance-enhancing drug use: first baseman Fred McGriff, closer Trevor Hoffman and outfielders Tim Raines and Vladimir Guerrero. The others: Bonds, Clemens, Bagwell, Sosa, Rodriguez and Gary Sheffield.

Yet for all the guys who used performance-enhancing drugs, the bulk of voters have spent years penalizing them, until changing their minds now.

I was among the minority of voters who cast my ballot for Bonds and Clemens when they first appeared in 2013. I was even among a smaller group, just 31 last year, who voted for Sosa.

Sure, Sosa wasn’t in Bonds’ class, but neither is any other hitter on the ballot. Sosa hit 609 home runs, the eighth most in history. He hit at least 50 homers in four seasons, produced at least 100 RBI in nine consecutive years and finished among the top 10 in the MVP race seven times, winning it in 1998.

Sosa could become the greatest slugger of the PED class who never publicly tested positive to be kept out of Cooperstown. His name was among the 104 anonymous positive test results in 2003, according to The New York Times.

The only man on this year’s Hall of Fame ballot to ever publicly test positive — and be suspended — is Manny Ramirez. He was suspended twice, 50 games the first time with the Los Angeles Dodgers in 2009 and 100 games in 2011 with the Tampa Bay Rays, effectively ending his major league career.

Ramirez might be one of the game’s greatest right-handed hitters, but he should never be in the Hall of Fame. He cheated when baseball actually had punishment for PED use. The suspensions severely damaged his team’s chances of winning without him.

The same goes for Alex Rodriguez when he comes eligible. He not only admitted to using steroids at two different junctures in his career, but he also received the longest drug suspension in baseball history, sitting out the 2014 season and costing the Yankees a shot at the playoffs.

The moment they were suspended, they blew their chance at Cooperstown.

It’s completely different with Bonds, Clemens or anyone else we suspect of steroid use but who never tested positive or was suspended. There were no rules before 2004. No signs in clubhouses banning PEDs. You were free to take whatever you desired with no testing, no penalties, nothing.

It’s as if you were on the highway and told there will be no police monitoring the stretch of road for the next 300 miles. Do you really believe you’d still go 55 mph?

We can’t retroactively establish rules guessing who used, who didn’t, how much or when.

The time has arrived to accept that Bonds and Clemens belong in the hallowed halls of Cooperstown.

Yep, just like a year ago with Piazza, who had to wait four years because of strong steroid suspicions. And Bagwell, who has waited six years, largely because of similar suspicions. And maybe Ivan Rodriguez, who could make it in his first year of eligibility.

They were great players from the steroid era.

Just not the greatest.

That legacy belongs to Bonds and Clemens.

One day, you’ll be able to see their plaques in Cooperstown, where they belong.

GALLERY: 2017 Hall of Fame candidates